Hacking Disney World FastPass+

2018-12-04

After clicking refresh hundreds of times over the course of a few days, my wife asked if I could show her how to write some code to check Disney World's FastPass+ availability. I started hacking on it, and before long, we had secured several FastPasses.

Disclaimers

This is a long, detailed, technical guide about reverse engineering a repetitive, manual process. It is targeted at software developers and focuses on the technical concepts, process, and even ethics. If you are here looking for an easy way to reserve your FastPasses, you will be disappointed; I am not providing a generally usable solution.

Hacking: Since this title may attract some non-developers or an overzealous lawyer thinking of sending me a cease & desist (apologies for calling you overzealous), let's clarify that "hacking" has multiple definitions. While it can be used to refer to circumventing software and/or security with malicious intent, it is also used among software developers to mean "quickly implementing or experimenting". I "hack" on random projects almost every week simply because I enjoy my craft in the same way a wood-worker may experiment with new ideas in their workshop for the love of building things. I have neither exploited nor discovered any security vulnerability in Disney's services. And I have taken care to ensure that my actions would not negatively impact Disney's services or guests.

Terms of Service: When tinkering with public websites, it's important to keep their ToS in mind. I'm no lawyer, and at the very least, a company could simply delete your account or otherwise block you from their service for violating their ToS, so you really should read the ToS when you wander off the beaten path. Disney's ToS currently has this interesting line: "Additionally, you agree not to access, monitor or copy, or permit another person or entity to access, monitor or copy, any element of the Disney Services using a robot, spider, scraper or other automated means or manual process without our express written permission." This is tricky, because while I am most definitely using an "automated means" to "access" and "monitor" the site, every user is most definitely using a "manual process" to achieve the same site access with the same goal. If I took this ToS literally, it basically says you can't access Disney Services at all without written permission which is obviously not what they meant. Like most legal documents, they've used broad language that gives them a way to object to pretty much any activity they don't like. My point here is: if Disney wants to, they will be able to craft a reason to delete, ban, or block access to Disney Services for using any of the techniques described in this post.

Liability: I have no affiliation with Disney, and nothing described in this post is approved by Disney. There are lots of ways that Disney could identify guests who leverage the techniques in this post, especially now that it's documented. If you attempt anything described here, you assume liability for any consequences resulting from your actions. I don't know how Disney handles such matters, but it's plausible that they could disable accounts, cancel reservations, or even bring forward legal action. If you're thinking about trying this yourself, go read Disney's ToS. Also, you should never copy, paste, and execute code from the Internet that you don't understand. Consider yourself warned.

With those disclaimers, let's dive in.

Understanding the request flow

First we want to understand how the FastPass availability data gets to the webpage. Given that the availability appears a few moments after the page renders, it's probably handled with an AJAX request flow. So we hop over to the FastPass page for Animal Kingdom, open our browser development tools, switch to the network panel, filter by XHR requests, and reload the page. Within a few seconds, we have a dozen requests to investigate.

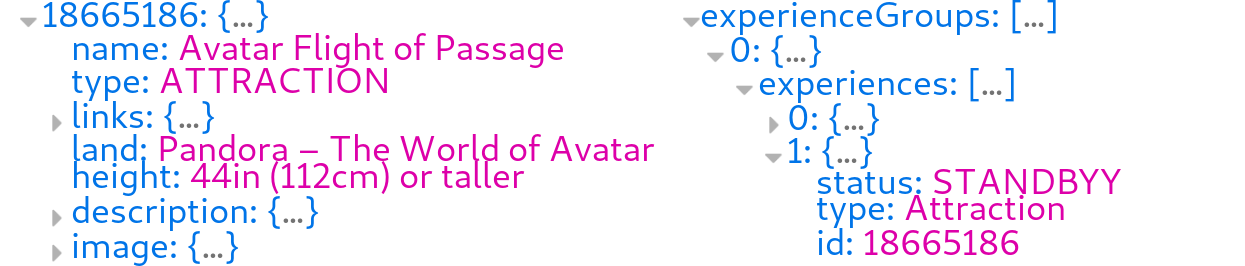

We click through the requests, examining their responses, and one of them jumps out as interesting. This JSON response has a bunch of details about several rides in the park and experienceGroups that seem relevant to our goal.

In the experienceGroups section, we find experiences that have an id and status. The id matches up to attraction IDs from assets section of the response, so we're able to infer that Avatar Flight of Passage has the ID 18665186. And we see the status field seems to have one of two values STANDBY or AVAILABLE. Now we're making progress. Let's figure out how to make this request ourselves.

That response came from a POST request to this URL: https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/en-eu/wdpro-wam-fastpassplus/api/v1/fastpass/orchestration/park/80007823/2018-09-16/offers;filter-time=09:00:00;guest-xids=CE04BE3E-0077-4AE1-911F-EF6509981CB9,240F2999-715D-415E-A0C5-C727BFD6CB75/.

/park/80007823is basically saying this request applies to a park with the ID80007823, which in this case is Animal Kingdom./2018-09-16is the date that we selected to look for FastPasses.filter-time=09:00:00identifies the time that we were looking for FastPasses.guest-xids=CE04BE3E-0077-4AE1-911F-EF6509981CB9,240F2999-715D-415E-A0C5-C727BFD6CB75/sounds like 2 UUIDs identifying the 2 guests that we had specified for the FastPass.

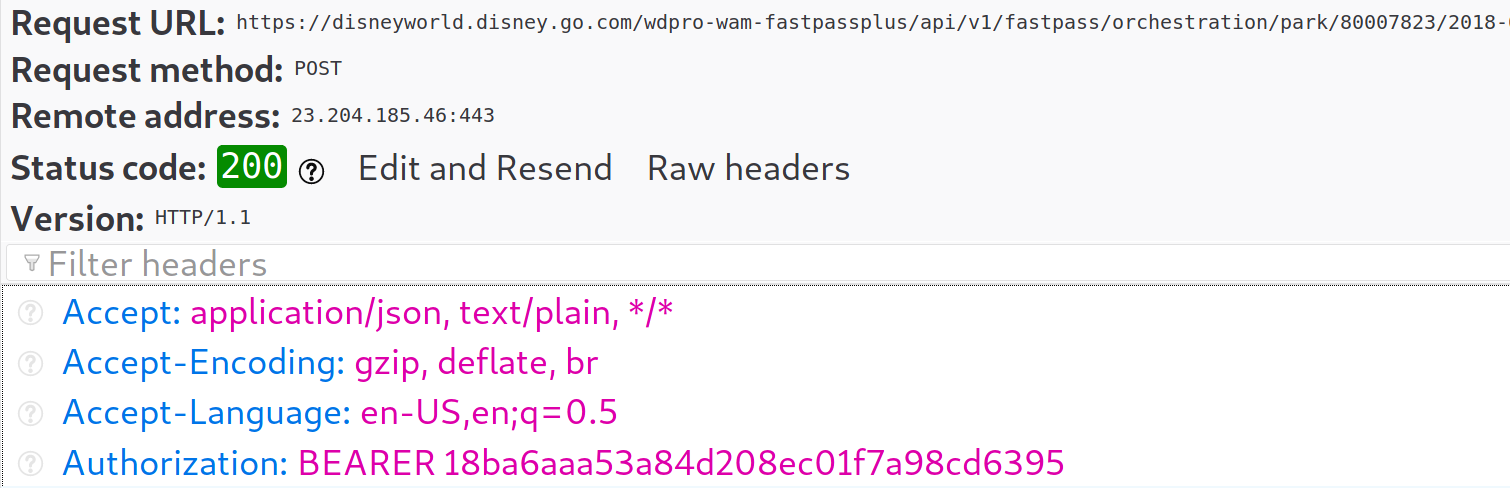

But before making HTTP requests to this API, let's take a closer look at the request to see if there is anything else we might need to include in our request.

Here we can see that the request contains an Authorization header that expects a standard bearer token, so we'll need to figure out how that token works. There are a couple places this token could come from, but the most common approach is to use session/cookie authentication to request it from another JSON endpoint. Sure enough, that's exactly what Disney engineers did. https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/en-eu/authentication/get-client-token/ sends back a token and an expiration field that has a value near 800. We open that URL and refresh a couple times to notice that the expiration appears to be counting down in seconds, so I'm guessing that this token has between a 15 and 30 minute expiration. It's a simple security measure that prevents you from storing that token and expecting it to work in other applications. But that's fine; I really didn't want to spend my evening disecting Disney's session authentication, and as long as we stay logged in, the browser will send cookies that Disney is probably using to authenticate our requests from the developer console. This makes it trivial to get an updated bearer token. Now we're armed with enough information to start automating this.

Automating the flow

First, let's set up a bunch of variables that we may want to swap out later to repeat this process with other dates, parks, rides, or guests.

var date = '2018-09-16'; var park = '80007823'; // This is Animal Kingdom var ride = '18665186'; // This is Avatar Flight of Passage var guests = ['CE04BE3E-0077-4AE1-911F-EF6509981CB9', '240F2999-715D-415E-A0C5-C727BFD6CB75']; // These are not our real IDs

Now we need to query for a bearer token. This is straight-forward:

// Query for the bearer token var tokenResponse = await fetch('https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/en-eu/authentication/get-client-token/').then(res => res.json()); var token = tokenResponse.access_token; console.log(token);

Now we're ready to query for the FastPass offers. Here's where we start plumbing in most of our variables. I went a step further and noticed that the FastPass reservation page for a single attraction adds a query parameter to limit the response to just that attraction. This is nice because it allow us to spelunk through less unrelated data when debugging each response, and it seems able to return more than just 3 availability times.

// Query for the FastPass offers var authorization = "BEARER " + token; var offersUrl = 'https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/en-eu/wdpro-wam-fastpassplus/api/v1/fastpass/orchestration/park/' + park + '/' + date + '/offers;start-time=09:00:00;end-time=12:00:00;guest-xids=' + guests.join(',') + '/?experienceId=' + ride; var fastPass = await fetch(offersUrl, { method: 'POST', headers: { 'Authorization': authorization, 'Content-Type': 'application/json;charset=UTF-8' } }).then(response => response.json()); console.log(fastPass);

Next, let's to dig through the experience groups to determine if the attraction has any FastPass availability. The filter condition on the experiences collection isn't necessary since we added the attraction ID as a query parameter above, but I had it sitting around from earlier iterations, so it's basically just extra validation.

function log(msg) { console.log(`${new Date().toLocaleString()}: ${msg}`); } try { var experiences = fastPass.experienceGroups[0].experiences var attraction = experiences.filter(attraction => attraction.id == ride)[0] if(attraction.status === 'STANDBY') { log('still standby'); } else { log('FAST PASS ' + attraction.status); } } catch() { log('still standby (availability not received)'); }

Once this is working, we wire up a system notification so that we're more likely to notice. It turns out Chrome notifications on MacOS are silent, but Firefox notifications are audible; it's not hard to guess which browser I ended up using.

// Once at the start of our script Notification.requestPermission() // When we find a FastPass that is available, this is how we trigger the notification new Notification('FAST PASS ' + attraction.status);

And now we want to fire off this check on an interval. This is where we want to be careful. I'm sure Disney wouldn't appreciate us firing off requests hundreds of times per second. I hope that they have rate-limiting in place, but I really didn't want to check because they may also have anomaly detection services looking to identify abuse of their APIs, waiting to alert oncall engineers or automated remediation systems that are standing by ready to disable your account for abuse. No thanks. I've chosen the very conservative rate of one request every 5 minutes.

So I wrapped up all our previous code into a function checkAttraction(park, ride, guests, date) and call that on an interval. I also call it once before the interval so that I don't have to wait 5 minutes to see the first successful request.

function checkAttractionInterval(park, ride, guests, date) { console.log("Checking ride " + ride + " fastpass availability every 5 minutes"); checkAttraction(park, ride, date, guests) var interval = setInterval(() => { checkAttraction(park, ride, date, guests) }, 300000); // 300,000ms is 5 minutes }

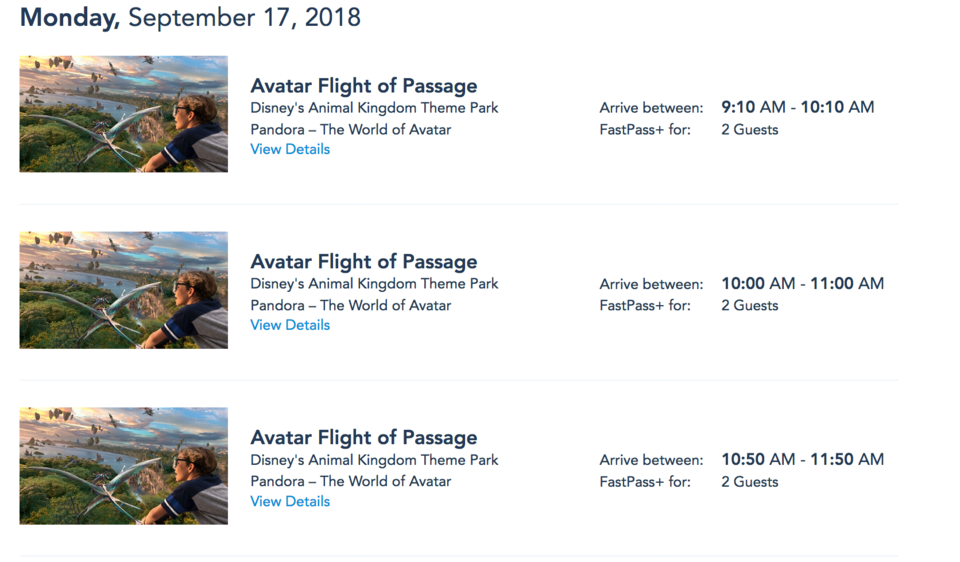

And sure enough, over the coarse of a couple days, we were notified of availabilities for a couple different rides. We even managed to score a pair of 2-person FastPasses for Flight of Passage for different people in our party at different times of day.

Iterative improvement

After we had FastPasses for the rides for some key rides, we wanted to take the process a step further. Initially, we focused on FastPasses in small groups (of 2 or 3 guests) and we were excited to get any time slot even if it meant splitting our party into a couple groups spread across different times of the day. Now we wanted to see if we could replace those FastPasses with ones that allowed our entire party to do it together or that was at more preferable times of the day. So I added more IDs to the guests variable, and I also modified the script to only notify us of FastPass time slots in a specific time window.

var startTime = '12:00'; var endTime = '16:20' try { var experiences = fastPass.experienceGroups[0].experiences; var attraction = experiences.filter(attraction => attraction.id == rideId)[0]; log(`${rideName} ${attraction.status}`); if(attraction.status === 'AVAILABLE') { var offers = attraction.offersets.map(o => { return { id: o.id, startTime: o.offers[0].startDateTime }}); var idealOffers = offers .filter(o => o.startTime > `${date}T${startTime}` && o.startTime < `${date}T${endTime}`) .sort((a, b) => a.startTime.localeCompare(b.startTime)); if(idealOffers.length > 0) { console.log(idealOffers) new Notification(`${rideName} FP+ ${attraction.status}`); } else { console.log(offers) } } } catch (e) { log(`${rideName}: no availability received`); }

At this point, I was feeling really clever, but occasionally we got notified of a time that didn't appear in the UI after refreshing. Upon comparing the websites HTTP response with the response from our script, I noticed that the script was returning FastPass offers that had a new field indicating conflicts. Struggling to understand the different times and the guest conflicts, I felt the need to go back to the beginning and compare the requests in more detail. I noticed the webpage was sending along a request body that included entitlementsToReplace.

Face-palm. How did I get this far without ever checking for a request body. It should have been obvious given that I had set Content-Type: application/json without sending a valid JSON body. I'm surprised the API didn't simply reject the requests. Anyhow, now I'm really learning how Disney's FastPass service works. My wife already knew that requesting FastPasses may involve surrending other FastPasses that you already have. But now I can see that the process of checking FastPass availability needs to be aware of which FastPasses would need to be relinquished so that it can create a set of fastpass offers. So we're back to spelunking through data to find these entitlements. I can't find any trace of them in previous API calls, so I start searching through cookies and local storage for the Disney domain. Finally, one of the IDs turns up in session storage with the key fpp.state.experienceCache.

So I piece together a snippet to collect the entitlement IDs.

var expCache = JSON.parse(sessionStorage.getItem('fpp.state.experienceCache')) var entitlementIds = expCache.existingExperienceData.entitlements .filter(e => e.facility === rideId) .filter(e => e.startDateTime.startsWith(date)) .map(e => e.partyGuests) .reduce((acc, val) => acc.concat(val), []) // For lack of flatMap support .filter(g => guestXids.includes(g.guestId)) .map(e => e.entitlementId); var body = JSON.stringify({ entitlementsToReplace: entitlementIds });

The date check here is a bit lazy, but good enough for my needs. And it tripped me up for a while, but the guest IDs in the experience cache were not the same ones used in the URL, so this didn't quite work until I realized I needed to track two IDs per person in our party. I did get a smile seeing that Disney engineers prefixed their new IDs with some clever hexadecimal: CAFEF00D. Now I'm not seeing guest conflicts in our API responses, the results are more accurate. As a bonus, we also see some times in the API response that don't appear in the UI.

Ethics of automation

At this point, we have a nice collection of code that checks the availability of FastPasses. Now I'm starting to consider the idea of letting the script automatically book our FastPasses, mostly to swap the ones we have for earlier time slots as they become available. Some (especially less technical individuals) will think I crossed an ethical line with my first line of code. Others will readily argue that any reasonable, non-malicious use of these APIs should be fair game. For me, automating the actual FastPass reservation is where the ethical questions weigh on me.

Spending several hours digging into a system and automating a boring, repetive process is far more stimulating and rewarding than sitting around clicking refresh for several hours. But it'd be naive to deny that it isn't an advantage over the long run. We're able to monitor FastPass availability passively for weeks. Is that fair? Devoted Disney World fans spend hours scouring Disney blogs and forums to find the ideal times to check for availability; is that a fair advantage? What defines a "fair" advantage vs an "unfair" advantage? If you say, "anybody can read Disney blogs to learn the strategy", I can argue "anybody can learn to write code." In fact, I believe basic programming should be required in highschool; it's arguably more valuable than Geometry, and everything in this blog post could be understood after a typical 12 week programming bootcamp.

Reverse engineering a system or automating a task isn't in-and-of-itself an ethical dilemma, but there are valid concerns around impacting the experience of other Disney guests, especially if hundreds or thousands of individuals were automating this. In many ways, this is similar to how factory automation has ethical issues around job displacement. And the AI revolution could do this on a much larger scale, and this ethical challenge is part of why I work in the AI industry. Should we ban AI? Should we ban factory automation? Should we ban automated driving? Should we ban automated gameplay? Should automated FastPass reservation be banned? I think it helps to understand the impact to humans and the intention of the activity.

Factories produce goods. Creating jobs was a by-product of factories, not the motivation. So it shouldn't be surprising that factories embrace automation. It has and continues to displace portions of the workforce, but it also contributes to higher standards of living. Ideally, we'd build systems that retrain people early enough to minimize displacement rather than merely trying to ban such automation. The same challenge is coming to the transportation industry where automated vehicles will usher in logistical progress and increased safety with the end of distracted or impaired driving, but are we helping truck drivers, taxis, and bus drivers prepare for job displacement?

But on the other end of the spectrum, games exist to profit from entertainment. They depend on human engagement and reward people for luck, time, or skill. Automation generally undermines this, and often degrades the experience for others. (There may be games that encourage automated agents, but they are still the exception.) It's no surprise that Disney's ToS identifies this explicitly by disallowing "automated gameplay".

So what's Disney's intent with online FastPass registration?

- If they intend for the FastPass+ website to be a game where humans to compete with sheer time and luck for the reward of coveted line-skipping, then I suspect I'll receive a cease & desist letter.

- If they intend for the FastPass+ website to be a progressive mechanism for distributing improved guest experiences, then I suspect the primary concern would be ensuring such automation doesn't unreasonably degrade the experience of other guests. (Of course, experience is often based on our perception and doesn't need to be based on objective reality.)

This doesn't have to be a dichotomy, but I wonder if the entire My Disney Experience website isn't itself detracting from the actual Disney World experience. Is the ideal Disney World experience: "click refresh on a website or app dozens of times per day for 60 days to ensure you can enjoy the attractions you care about"? Is Disney trying to reward people who read the most Disney forum discussions? I'd bet that within a decade the My Disney Experience portal shifts to generating custom park intineraries including auto-reserved FastPasses, scheduled character visits, restaurant reservations, and your own personal AI assistant all based on your preferences, profile, or wallet. Of course there will be "Create your own adventure" options for recovering Farmville-addicts who want to click the same button five hundred times to earn rewards, but realistically, machine learning could already plan a better Disney itinerary than the most devoted Disney World fans if Disney put the right minds behind it. This is exactly the kind of work my company helps Fortune 100 companies achieve every day.

...but I've digressed from an elaborate self-justification to a tangent on Disney World's business strategy. Overall, I'm reasonably convinced that I am not negatively impacting Disney services or guests, and that I'm still operating consistent with the intention of the FastPass+ website, so I'm content to continue this endeavor into the final stretch: Automated FastPass Reservations.

Automating the last mile

I wasn't sure what to expect for this step. I was imagining obfuscated API calls through complex workflows, but the FastPass+ backend engineers designed an API that made this almost too easy to work with. Watching the network tab in my browser, I simply manually booked one FastPass that had lots of availability. A simple POST request to https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/wdpro-wam-fastpassplus/api/v1/fastpass/orchestration/offer/357924375465/ with an empty JSON body is all it seemed to take. That number is the very same offer ID that my previous code was logging. I refactored the previous code to return the offer ID, and made sure to clear the interval to avoid a loop that keeps alternating between a couple reservations.

clearInterval(interval); // Stop the periodic check var token = await getToken(); var response = await fetch(`https://disneyworld.disney.go.com/wdpro-wam-fastpassplus/api/v1/fastpass/orchestration/offer/${offerId}/`, { method: 'POST', body: '{}', headers: { 'Authorization': 'BEARER ' + token, 'Content-Type': 'application/json;charset=UTF-8' } }); if(response.ok) { log(`${response.status} Successfully booked FP offer ${offerId}`) } else { log(`${response.status} Failed to book FP offer ${offerId}`) console.log(response.text()) }

And that's it! This was almost too easy. I did test this step more extensively on FastPasses we didn't care about, because I don't think my wife would have been happy if I messed up our existing Avatar: Flight of Passage reservations. Finally, we configured it to try and rebook half our party for Avatar at an earlier time (to line up with the rest of our party). It ran overnight, and the next morning the notification fired. Moments later, it was reserved. In the end, after running the script for a few weeks, we were able to narrow in FastPasses for our whole party in a relatively small window of time.

Rinse and repeat

What more could I possibly do? I was asked if it was possible to automate dining reservations at Be Our Guest. I basically restarted this process, breaking down the request workflow that goes into dining availability. The process was a bit more convoluted:

- Instead of a token returned by an API, I had to dig a CSRF token from the DOM (

document.getElementById('pep_csrf').value). - Each booking time option had a different range of values. I found that "brunch" and 2pm were enough to check all non-dinner hours.

- The API used form data instead of JSON so it was a bit clunkier to work with.

- The API returned HTML that I had to parse to figure out availability availability.

I did manage to hack together something in about an hour to check for availability. Over the course of about 3 weeks, it did help us book lunch reservations at Be Our Guest, though we did have to book it in three separate smaller reservations because we never found a reservation for 10. I didn't try to automate booking though. It involves a multi-page form submission process including credit card number submission and confirmation of having read the booking terms. Is this automatable? Absolutely. But while the FastPass APIs made for a fun hack for a pair of evenings, the dining reservation APIs are the kind of APIs you would only want to use because your employer pays you to. At this point, I had already moved onto new unrelated projects.

Post-mortem

We used FastPasses a lot on our trip. We made lots of changes mid-day from the park, but we also used this code to change fastpasses from the resort in our downtime. I did spend another 30 minutes fixing issues when my code stopped working. It seems Disney had made 2 breaking changes:

- Authentication was failing without the cookie header (perhaps the team saw our unusual cookie-less requests). Fixing this was a simple as adding

withCredentials: trueto the axios requests because we were still running this from the browser session. - All our guest IDs were wrong. Where I had previously found that guest IDs in the URL were different from the guest IDs in the experience cache, it turns out the API changed which guest ID was needed in the URL. It wasn't hard to fix, but it is interesting because my wife noted that the Disney World forums were discussing issues with MDE (My Disney Experience) a week or so before our trip. I wonder if they had dependent services that weren't updated to account for this breaking change.

So basically the code snippets in this blog were already out-of-date by the time I posted it. But honestly, none of that really matters. We had a great time at Disney World, and we ended up releasing several Flight of Passage FastPasses to get a few more rides on the Seven Dwarf Train.

This hack wasn't about perfecting a family vacation, rather our vacation afforded me an opportunity to enjoy my craft. But you should definitely invite a software engineer on your Disney World trip.